Transcript of the English Presentation

Identifying "Mona Lisa" with the Help of Contemporary Historical Sources of the 15th and 16th Centuries and the Tools of Anthropology

Abstract:

The question "Who is Mona Lisa?" could have been answered centuries ago, if the language of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the symbolism, had not already been forgotten by the 17th century. Once more we must learn this language used by our forefathers over thousands of years of history. The dress and the Sforza symbols shown at the upper part of the neckline of "Mona Lisa" tell us that the depicted lady is in fact Isabella of Aragon (1470-1524), daughter of King Alfonso II of Naples and wife of Duke Gian Galeazzo II Maria Sforza of Milan. However, we are nowadays so distant from the truth regarding "Mona Lisa" and the life of her great court painter Leonardo da Vinci that it is no longer enough to support this theory with contemporary written and pictorial historical sources. We need the help of anthropology.

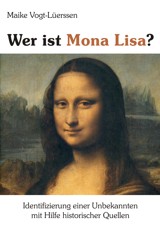

The most famous portrait painting in the world can be found in the Louvre museum, Paris, under the name of "Mona Lisa" (Fig. 1). During the research for my book "Who is Mona Lisa? In search for her identity"1 and ongoing further investigations, it became apparent that what had been promoted as historical facts about the identity of "Mona Lisa" for over a hundred years were merely assumptions. Critical thinking about this painting has become a rarity. Careful library research, however, has shown that the answer to the question, "Who is Mona Lisa?", could have been answered centuries ago.

Up to the present day it has been thought that the art historians are the experts regarding the portrait paintings of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Yet their primary tool, the history of stylistic art (in German: Stilgeschichte or Bildgenese), is not suited for determining who is depicted on a painting of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, because analysing the strokes of the brush of the artists cannot give us any information about the identities of the depicted and about the exact time when their portraits were made. Consequently, the works of so-called pioneers of a particular style and of good imitators are often dated incorrectly. It cannot even give us 100% certainty that we really found the painter who made this piece of art.2

As a case in point, the majority of the works of the greatest female painter of the Renaissance, Sofonisba Anguisciola or Anguissola (1532-1630) were – until 1995 – attributed to her male colleagues such as Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, Coello, Moroni, Tintoretto, Bassano, Salviati, Bronzino, Carracci, Zurbarán, Murillo, Sustermans and van Dyck. This was corrected in 1995, when the Art Museum (Kunsthistorisches Museum) in Vienna exhibited her paintings for the first time under her name to the public.3 Likewise happened to Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), whose works were erroneously attributed to students of his such as Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1466/67-1516) or later Italian artists such as Giovanni Cariani (ca. 1490-1547). Unlike Sofonisba Anguisciola, however, these mistakes have yet to be corrected. For instance, Leonardo’s self-portrait (Fig. 2), which can be seen at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is still attributed to Giovanni Cariani, even though the fashion of the depicted person is typical for the 70’s and 80’s of the 15th century, as any expert of the history of the costume can confirm. Giovanni Cariani was not even born at that time.

For the correct identification of the men and women and the children depicted in Renaissance paintings and the correct dating of these works we have to be equipped with the following knowledge:

- the history of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance;

- the traditions and customs of these historical epochs;

- the history of the costume – what was in fashion at what time and where;

- the high dynasties of the 15th and 16th centuries and all their members, male and female; we have to collect descriptions of the various members of the high dynasties from as many primary and secondary historical sources as possible;

- the coat of arms and the specific colours and symbols (also called emblems or devices) of these high dynasties.

It is also essential to use the relevant primary written historical sources in a scientifically correct way to confirm our theory about a portrait or a painting. Only if these written historical sources contain a detailed description of a portrait or a painting that is the subject of a research should we be allowed to use them as evidence for our theory. If these historical sources give no information about the facial features, the style of the hair and its colour, or the costume and the background of the depicted person, then they cannot support the opinion of the researcher with respect to the identity of the sitter.4

As with so many paintings and drawings (over 95%) that originate from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the world-renowned portrait called "Mona Lisa" is neither signed nor dated nor do we have any written historical source telling us who the depicted person is. The title "Mona Lisa" was given to the painting by Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588-1657), an art lover and secretary of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, in 1625.5 The true identity of the depicted lady had already been lost by that time. Whilst we can be very certain that this masterpiece was created by the famous court painter of the mighty Milanese dynasty of the Sforza, the Florentine Leonardo da Vinci, the date of its creation and the person that it depicts remained a mystery for a long time. Leonardo’s numerous notebooks are filled with hundreds of his ideas, his mathematical formulas and computations, his sketches of technical innovations, his drawings of heads, limbs, animals and plants, and even his household costs, but only with very few truly personal entries.

For many years we have repeatedly read in articles, books and newspapers that Lisa Gherardini (1479-?1551), the eldest daughter of Antonmaria Gherardini and wife of the Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo (1465-1538), is the mysterious lady in the famous painting "Mona Lisa". Yet for this claim, made by the German art historian Frank Zöllner, no supporting historical source can be found. However, it is no question that Leonardo da Vinci made a silverpoint drawing of at least a head without hair of a certain Mona Lisa in 1503.6 Leonardo’s father, Ser Piero da Vinci († 1504), who knew the merchant’s family of the del Giocondo in his role as their notary very well could have taken the role as the intercessor for one of its numerous members.7 The del Giocondos were a big family. Besides Francesco del Giocondo there were his brothers Giocondo and Giuliano, his first cousins Paolo, Iacopo, Amadio, Zanobi and Benedetto, and his second cousins, the male descendants of a certain Paolo del Giocondo, for example Piero Francesco del Giocondo (1460-1512/1528).8 Many of them were working in the family business. The silverpoint drawing of the head of Mona Lisa and presumably also the portrait of her husband – it was common for merchants and patricians in the Renaissance that husbands and wives or brides and grooms were painted in two individual portraits – would have never been produced by Leonardo da Vinci without the intervention of Ser Piero da Vinci. According to the statements of Anonimo Gaddiano, a contemporary of Leonardo, only a portrait of a certain Piero Francesco del Giocondo was made by the great master: "He made a portrait of Piero Francesco del Giocondo [not of Francesco del Giocondo] from life".9 Anonimo Gaddiano did not know anything about a portrait of the silk merchant’s wife.

When Ser Piero da Vinci deceased in 1504, there was nobody who could force Leonardo to complete the portrait of the wife of Piero Francesco del Giocondo. Hence it remained unfinished, as contemporaries have reported. We know this from the eminent manuscript of the painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), "Lives of Seventy of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects", which was first published in Florence in 1550.10 A second, improved edition followed in 1568.11 Giorgio Vasari, who did not know Leonardo da Vinci in person, visited Francesco da Melzo at Milan or at Vaprio d’Adda to obtain information about the great painter and his works. The latter went down in history as "Leonardo’s favourite pupil". About the portrait of Mona Lisa, Giorgio Vasari, who is known for mixing up people in his biographies12, eventually writes the following: "For Francesco del Giocondo, Leonardo undertook to paint the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife, but, after loitering over it for four years, he finally left it unfinished. This work is now in the possession of King Francis of France [this king died in 1547], and is at Fontainebleau. Whoever shall desire to see how far art can imitate nature, may do so to perfection in this head, wherein every peculiarity that could be depicted by the utmost subtlety of the pencil has been faithfully reproduced. The eyes have the lustrous brightness and moisture which is seen in life, and around them are those pale, red, and slightly livid circles, also proper to nature, with the lashes, which can only be copied, as these are, with the greatest difficulty; the eyebrows also are represented with the closest exactitude, where fuller and where more thinly set, with the separate hairs delineated as they issue from the skin, every turn being followed, and all the pores exhibited in a manner that could not be more natural than it is: the nose, with its beautiful and delicately roseate nostrils, might be easily believed to be alive; the mouth, admirable in its outline, has the lips uniting the rose-tints of their colour with that of the face, in the utmost perfection, and the carnation of the cheek does not appear to be painted, but truly of flesh and blood: he who looks earnestly at the pit of the throat cannot but believe that he sees the beating of the pulses, and it may be truly said that this work is painted in a manner well calculated to make the boldest master tremble, and astonishes all who behold it, however well accustomed to the marvels of art. Mona Lisa was exceedingly beautiful, and while Leonardo was painting her portrait, he took the precaution of keeping someone constantly near her, to sing or play on instruments, or to jest and otherwise amuse her, to the end that she might continue cheerful, and so that her face might not exhibit the melancholy expression often imparted by painters to the likenesses they take. In this portrait of Leonardo’s, on the contrary, there is so pleasing an expression, and a smile so sweet, that while looking at it one thinks it rather divine than human, and it has ever been esteemed a wonderful work, since life itself could exhibit no other appearance."13

When you compare the above statements of Mona Lisa’s face – there is no mentioning of her hair, her dress and the background of her portrait – with the face of the "Mona Lisa" in the Louvre, you will find no similarities other than that lovely smile which is actually exhibited by most of the female faces drawn by Leonardo. The "Mona Lisa" in the Louvre is missing the eyebrows, the lashes and the rosy nose openings, and Leonardo also did not seem to have afforded much care for her throat-pit.

Moreover, Vasari describes the portrait of Mona Lisa as "unfinished" in both editions of his biographies, that is 31 years, respectively 49 years, after the death of Leonardo da Vinci. In this instance the art historians of today accuse Vasari of not being well informed. However, they have no historical sources to support their allegation. Vasari also describes another very famous work of the great master, "The Adoration of the Magi", as "unfinished", and everyone can see that in this case he is correct. Vasari writes: "A picture representing the Adoration of the Magi was likewise commenced by Leonardo, and is among the best of his works, more especially as regards the heads; it was in the house of Amerigo Benci, opposite the Loggia of the Peruzzi, but like so many of the other works of Leonardo, this also remained unfinished."14

In January 2008 a newly discovered contemporary historical source of the 16th century in the University of Heidelberg, Germany, finally confirmed that the "Mona Lisa" at the Louvre could not be the Florentine merchant’s wife Lisa Gherardini. A friend of Leonardo da Vinci and owner of a Cicero edition, printed in 1477, Agostino Vespucci, wrote the following in the margins of his book: "Apelles pictor. Ita Leonardus Vincius facit in omnibus suis picturis, ut enim caput Lise del Giocondo et Anne matris virginis. Videbimus, quid faciet de aula magni consilii, de qua re convenit iam cum vexillifero. 1503 Octobris (in English: The painter Apelles. In this way Leonardo da Vinci makes it in all his pictures, for example the head of Lisa del Giocondo and of Anne, the mother of the Virgin. We will see what he is going to do with regard to the great hall of the Council about which he has just agreed with the Gonfaloniere. October 1503)."15

Leonardo da Vinci did not draw the head of Lisa Gherardini (1479-?1551), the eldest daughter of Antonmaria Gherardini and wife of Francesco del Giocondo, but of her sister-in-law Lisa del Giocondo (1468-?1542)16, the third daughter of Bartolomeo del Giocondo, younger sister of Francesco del Giocondo and wife of Piero Francesco del Giocondo. It was not until Protestantism gained widespread acceptance in Western and Middle Europe in the second half of the 16th century that women in the Protestant states finally lost the last piece of their identity, their own surname – the family name of their ancestors –, when they became married. Not even the wives of the well-known reformers of the first half of the 16th century like Katharina von Bora (1499-1552), the wife of Martin Luther, Idelette de Buren (1507-1549), the wife of Johannes Calvin, Elisabeth Silbereisen († 1541), the wife of Martin Bucer, and Wibrandis Rosenblatt (1504-1564), the wife of Johannes Oecolampadius, Wolfgang Capito and Martin Bucer, to name only a few, had to give up their own surnames when they married their famous husbands. Katharina von Bora, for example, died as Katharina von Bora and not as Katharina Luther in 1559, 27 years after her marriage. In the Catholic states like Belgium and Spain married women never had to change their surnames. In Italy the change of the surname of married women was introduced as recently as the 70’s of the 20th century (Art. 143 bis Cognome della moglie: La moglie aggiunge al proprio cognome quello del marito e lo conserva durante lo stato vedovile, fino a che passi a nuove nozze). Yet in every important document like the passport or the driver's license the Italian women still have to use their own surnames and not the surnames of their husbands.

In the 16th century no Italian woman lost her own surname that she had since her birth as a result of marriage. Lisa Gherardini, too, did not give up her surname when she became married to Francesco del Giocondo. Her surname was part of her identity. Even as wife of Francesco del Giocondo, her name was always Lisa Gherardini and never Lisa del Giocondo. The actual Lisa del Giocondo, a sister-in-law of Lisa Gherardini, was born in 1468 and was already 35 years old when Leonardo da Vinci made the silverpoint drawing of her head in 1503. Because of her age she can definitely be ruled out as a candidate for the "Mona Lisa" at the Louvre.

In order to identify the depicted lady at the Louvre one must be aware that until the first half of the 16th century only a minority of the population in Europe (less than 10%) was able to read and write. If someone in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance wanted to leave a message that everyone could understand, they had to use symbolism, "the pictorial language", already deployed over thousands of years by their forefathers. For example, the stories in the Bible, which only a few were able to read, were painted as pictures on the walls of the churches so that everyone could appreciate them. The members of the high and the low dynasties and even the rich and wealthy merchants and patricians had their specific coats of arms, symbols (also called emblems or devices) and colours with which they decorated their clothes and their portraits and with which they could easily be identified. Progressively more people of the 15th and the 16th century had enough money to pose for a portrait, which would survive their death and which would tell us, the people of the future, what they looked like and who they were. Through these portraits their greatest wish, "to live forever", could be fulfilled.

Yet we people of today have forgotten the "pictorial language" of the past, the symbolism. We have to relearn the specific coats of arms, symbols and colours of at least the high dynasties – over 80% of the depicted in Renaissance paintings are members of the high dynasties17 – so that we, like the heralds in the past, can identify the men and women depicted on the Renaissance paintings. During the Middle Ages, these heralds were highly regarded, as they were capable of identifying any nobleman, even those completely hidden from head to toe under heavy armour, like for instance Lord Hartmann of the Aue (Fig. 3), by their coats of arms. These coats of arms were composed of the main symbols and the specific colours of their dynasties and decorated their shields, the saddle-cloth of their horses, their lances, their robes and often also their helmets. The heraldic figures, often animals and plants, seen on the coats of arms, which became hereditary in France towards the end of the 11th century, turned into the permanent insignia of the family or dynasty during the 13th century. Thus, after enduring about 7 - 8 years of schooling, heralds could attribute any coat of arms to a specific family or dynasty.

The portrait paintings of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance disclose to us the identity of the depicted through their coats of arms, symbols and colours. The higher the status of the depicted, the more complex the coat of arms became during the 15th century. In Figure 4, we observe the wedding of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy (1396-1467) and his third wife, Isabella of Portugal (1497-1471/72), in 1430. The specific coats of arms of the groom, the bride and their witnesses at their wedding were added to the painting. In this case, knowing the coats of arms of the high nobility of the 15th century means knowing who was present at this important ceremony. To make the identification easier the depicted sometimes only used their main symbols on their paintings, as the mighty Milanese dynasty of the Visconti already did in the second half of the 13th century.18 Note how in Figure 5 the Seven Electors of the Holy Roman Empire can be easily identified through their simple main symbols above them: the Archbishop of Cologne, the Archbishop of Mainz, the Archbishop of Trier, the Palsgrave of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the King of Bohemia (from left to right).

Certain high dynasties like the Milanese dynasties of the Visconti and the Sforza produced many distinct symbols during the 13th, 14th and/or 15th century. They both became the masters in using these in their portrait paintings. As a result, we are able to identify each of the 85 members of the main line of the Sforza. The Visconti had at least 19 symbols and the Sforza, who were using the Visconti ones as well as their own, had at least 31 symbols with which they decorated their portraits.19 Almost everyone of these symbols also had different ways of being displayed. For example, the Sforza symbol of the quince could be shown on a painting or on a fresco as a pear- or an apple-like fruit, as a pink flower or as an inferior ovary.20 Of course, all court painters of the Visconti and the Sforza were acquainted with the symbols of these dynasties, which they often added to relevant portraits.

Leonardo da Vinci, who was one of the main court painters of the Sforza at least for 18 years from 1482 to 1500, was likewise very familiar with the specific symbols and the specific colours of these mighty dynasties. Given that he was a court painter of the Sforza for so many years, we should expect that the depicted lady at the Louvre is a member of this Milanese dynasty. Indeed, this lady can be easily identified as a member of the Sforza through the dress she is wearing and through the symbols which decorate the upper portion or neckline of her dress. According to a written historical source, she is wearing the mourning dress of the second phase of the one-year mourning period of the Sforza Duchesses of Milan: "... a dress of dark green with two sleeves of black velvet and a veil on the head which covers her to below the eyes, and the usual headdress beneath it."21 Naturally, the veil of "Mona Lisa" is shorter than the described one. After all, this is a portrait, and the most important part of any portrait are the eyes of the depicted. The historian Gregory Lubkin tells us that this kind of dress was worn by the Milanese Duchesses Bianca Maria Visconti (1425-1468), the wife of Duke Francesco Sforza, and Bona of Savoy (1449-1503), the wife of Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza, in the last three months of the one-year mourning period. For the first nine months only black dresses and no jewellery were permitted. The latter was also forbidden in the next three months, whilst the Milanese Duchesses of the Sforza could at least change the black dress into that which the famous lady at the Louvre is wearing.22

We have only five candidates who were allowed to wear this kind of dress: Bianca Maria Visconti (1425-1468)23, Bona of Savoy (1449-1503)24, Isabella of Aragon (1470-1524)25, Beatrice d’Este (1475-1497)26 and Christina of Denmark (1521-1590)27. Of all these five Milanese duchesses of the dynasty of the Sforza we possess many portraits. Thus the depicted lady "Mona Lisa" at the Louvre has to be Isabella of Aragon (Fig. 6), the daughter of Alfonso II of Aragon, King of Naples, and Ippolita Maria Sforza, and the wife of Duke Gian Galeazzo II Maria Sforza (1469-1494). The portrait of Isabella of Aragon in Figure 6 is extraordinary, because the painter Bernardino Luini used letters to state her name, which was still very rare in the 16th century. Isabella of Aragon was one of the most famous Italian women of the 15th and 16th century. She was the only woman who, according to the author Paolo Giovio († 1552), had the privilege to be mentioned in his highly appraised 16th century book "Vitae virorum illustrium", in which otherwise only the lives of famous men of the Renaissance were described.28 Even though this knowledge about Isabella of Aragon was lost by the first half of the 17th century, many portraits of her survive until today – in fact, we still have over 250 portraits of her (Fig. 7).29 They tell us in minute detail the story of her life.

Leonardo da Vinci depicted Isabella of Aragon on her most famous portrait painting, "Mona Lisa", not only with the ducal Sforza mourning dress of the second phase, he also equipped it with specific Sforza symbols. At the upper portion or neckline of her dress we see a chain of interlinked rings and below this an intricate pattern, which is very characteristic for Leonardo da Vinci (Fig. 8). It is his own creation of a new Sforza symbol, which was only used by him. It is a kind of personal signature, and thus we know the painting of "Mona Lisa" was made by him. As inspiration for this new Sforza symbol probably served the depiction of the Visconti symbol of the star-like sun on an altarpiece from the first half of the 14th century (Fig. 9). On this religious painting the illustrious and highly esteemed Galeazzo I Visconti (1277-1328) lent his face to the Virgin. Until the appearance of Regina della Scala († 1384), the wife of Bernabo Visconti, only male members of the Visconti were allowed to lend their faces to the saints, both the male and female ones. Following the extraordinary Regina della Scala, the female members of the Visconti and of the Sforza lastly also attained the right to lend their faces to the female saints, including the Virgin. The male members of the Visconti and of the Sforza lent their faces from now on only to the male saints with the exception of one female, Saint Anne.30

The Sforza symbol of the chain of interlinked rings is one of the most interesting devices of this dynasty because of its origin and of its history of changes over four generations. It started with a single diamond ring, which Niccolò III d’Este († 1441), Margrave of Ferrara, presented to the great Condottiere Muzio Attendolo Sforza (1369-1424), the father of Francesco Sforza, as a friendship symbol for his help against his great enemy Ottobuono Terzo, the tyrant of Parma. When Niccolò III d’Este presented this symbol also to the Medici as a token of friendship, the Sforza had to modify it to avoid confusion when decorating their members with this symbol on their paintings. Therefore, under the Milanese Duke Francesco Sforza (1401-1466) and his eldest son and successor, Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1444-1476), the diamond ring was used in three different forms: 1. as a single diamond ring, which was held in the claws of an old man who had a long beard and a body of a dragon (Fig. 10: Francesco Sforza and some of the main Sforza symbols); 2. as three interlinked diamond rings, which symbolized the friendship between the Sforza, the Visconti and the Borromeo (Fig. 11: Bianca Maria Visconti’s dress has been decorated with the three interlinked diamond rings) and 3. as a chain of interlinked diamond rings (Fig. 10: the chain of interlinked diamond rings can be seen under the body of the old man with the single diamond ring; and in Fig. 12).

The mythological painting with the woman in Figure 12, who is lending her face to the Greek Goddess Pallas, is an identification portrait. Her dress displays: 1. many sets of three interlinked diamond rings, 2. one chain of interlinked diamond rings (at the neckline of her dress), 3. one large and a number of small single diamond rings and 4. many sets of four interlinked diamond rings. Hence this woman must be associated with the Sforza dynasty (three interlinked diamond rings and the chain of interlinked diamond rings) and with the Medici dynasty (the single diamond rings). Taking a look at the family trees of the Sforza and the Medici we can see that no female member of the Medici ever married a member of the Sforza, but that one female member of the Sforza married a member of the Medici. Her name is Caterina Sforza (1463-1509). She was the famous Countess of Imola and Forlì, the female warrior of the Sforza, and she married Giovanni de’ Medici (1467-1498) in 1497. The painter, a pupil of Sandro Botticelli, even invented a new symbol for her: the Sforza symbol of the three interlinked diamond rings and the Medici symbol of the single diamond ring make four interlinked diamond rings. This new symbol could only be used by Caterina Sforza. Thus when we see four interlinked diamond rings on any painting of the Renaissance we know the depicted lady has to be Caterina Sforza.

When Lodovico il Moro Sforza (1451-1508), the fourth son of Francesco Sforza, became the mightiest man in Milan in 1478, the symbol of the diamond ring was modified again. It became a chain of large interlinked rings without the diamond for the male members of the Sforza (Fig. 13) and a chain of small interlinked rings without the diamond for the female members of the Sforza, as depicted as embroidery on the dress of "Mona Lisa" (Fig. 8). Only Bianca Maria Sforza (1472-1510), cousin and sister-in-law of Isabella of Aragon, had the right to wear a chain of medium-sized interlinked rings, because she was married to the Emperor Maximilian I (Fig. 14). If Isabella of Aragon had not been in mourning when her famous portrait was made, she would have been decorated with a real chain of small interlinked rings like Violanta Bentivoglio († c. 1550) (Fig. 15) in her portrait, who was married to Gian Paolo Sforza (1497-1535), a son of Lodovico il Moro Sforza.

Regarding the renowned portrait of Isabella of Aragon at the Louvre, we not only know who painted it and who is depicted on it, we can also determine when the original painting was made. Isabella of Aragon was Duchess of Milan from 1489 to 1494. Solely at this time was she allowed to wear the ducal mourning dress, and there was only one important death that could trigger this. Her mother, Ippolita Maria Sforza, died on 19 August 1488. Hence Isabella of Aragon must have worn this specific Sforza ducal mourning dress of the second phase from the 19 May to the 19 August 1489. It is the official portrait of the new Duchess of Milan, Isabella of Aragon, and was made at her castle of Pavia. This claim is supported by the background scenery of the painting.31 But the "Mona Lisa" at the Louvre is not the original one of 1489, which was furnished with two columns, as were all portrait paintings made at the castle of Pavia (Fig. 16). The "Mona Lisa" is a later copy painted by Leonardo da Vinci for his own personal use.

The Visconti and the Sforza were the masters in using their specific symbols to tell us not only who is who in their dynasties, but also very private details about them; for instance, how many sons and daughters they had. Personal information that was either never written down or got lost over the last five to eight hundred years is still preserved in their paintings. Consequently, we can learn one of the greatest secrets of Isabella of Aragon: she was married twice and had eight children. When her first husband, her cousin Gian Galeazzo II Maria Sforza, died in 1494, with whom she had three children, the son Francesco Maria Sforza or Francesco il Duchetto (1492-1512) and the daughters Bona Maria Sforza (1493-1557) and Ippolita Maria Sforza (1494-1501), she married in great secrecy her favourite court painter and closest friend Leonardo da Vinci in June 1497 (probably on the 24th).32 It was a so-called clandestine marriage, and only a few people knew about it – we will not find any documents about it in the Italian archives –, because it was seen as a great malfeasance for a lady of her status to do so. Isabella of Aragon, the former Duchess of Milan and daughter of a king, married far below her status. She was not a weak woman: not without reason was she mentioned as the only woman in the celebrated book of Paolo Giovio about the famous men of the Renaissance. She knew what she did. She married Leonardo da Vinci because she loved him very much.

According to the pictorial contemporary sources, Isabella of Aragon and Leonardo da Vinci had five children: Francesco (1498-1570), Count of Melzo (Fig. 17), Giovanna (1502-1575) (Fig. 18), Duchess of Paliano, Maria (1503-1568) (Fig. 19), Margravine of Vasto and of Pescara, Antonio (1506-1543) (Fig. 20), Duke of Montalto, and Isabella the Younger (c. 1510-after 1540) (Fig. 21), Princess of Squillace.33 We are still in the possession of a copy of a written contemporary source, in which Francesco da Melzo called Leonardo da Vinci his father: "He was to me the best of fathers ..."34 The genealogists of the past and of today committed major mistakes with respect to the children of Isabella and Leonardo. Since they found no Francesco da Melzo wherever they looked, they equated Francesco da Melzo with a certain Giovanni Francesco da Melzo. However, Francesco da Melzo was never named Giovanni Francesco da Melzo in any written historical source, and he belonged to the Melzo di Sforza or Melzo da Vavero and not to the Lamberghis de Melzo, as Giovanni Francesco da Melzo did.35 The same happened with Leonardo’s second son Antonio, the Duke of Montalto, who was equated with an "Antonio of Aragon" who was a son of an uncle of Isabella of Aragon, Ferdinand of Aragon. Even though Leonardo’s son Antonio was born in 1506 and died in 1543 and Ferdinand of Aragon’s son Antonio was born in 1499 and died in 1553, the genealogists declared that these persons were one and the same.36 Leonardo’s and Isabella’s daughters Giovanna and Maria were very close to their brother Antonio. Therefore they were also declared as children of Ferdinand of Aragon, although he had no daughters at all. Only for the youngest child of Leonardo and Isabella, their daughter Isabella the Younger, the genealogists gave up the quest to find her parents. Thanks to her we know the original title of each of Isabella’s and Leonardo’s five children: Prince or Princess of Milan and Aragon.

We are nowadays so distant from the truth concerning "Mona Lisa" and Leonardo da Vinci that it is no longer sufficient to support a theory with written and pictorial historical sources. The help of anthropology is needed. With the tools of this discipline we can reconstruct the face of Isabella of Aragon, who is buried in the Church of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples. We can compare the mitochondrial DNA of her with her children Maria and Antonio, who lie next to their mother, and we can also reconstruct their faces. It is worth noting that Ferdinand of Aragon, the alleged father of Antonio and Maria, is not buried in San Domenico Maggiore. We should in fact also look for Leonardo da Vinci here37. He was never buried in France. It is most likely that in August 1519 his bones were brought to this church, which may also be the burial place of Isabella’s eldest son by her first husband, Francesco Maria Sforza (Fig. 22), and of the famous poetess Vittoria Colonna (1492-1547) (Fig. 23), a very dear friend of the family.

List of Images:

- Leonardo da Vinci, "Mona Lisa", 1489, Paris, Louvre

- Leonardo da Vinci, Self-Portrait, c. 1480, Washington, National Gallery of Art

- Lord Hartmann of the Aue with his coat of arms, which can be seen on his shield, his robe, the saddle-cloth of his horse, his lance and his helmet, Codex Manesse, 14th century, plate 6

- Miniature from the Remissorium Phillippi, The Hague, Algemeen Rijksarchief

- The Seven Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, Codex Balduini Trevirensis, Koblenz, National Archives

- Bernardino Luini, Isabella of Aragon, Duchess of Milan, Milan, Castello Sforzesco

- First row from left to right: Leonardo da Vinci (wrongly attributed to Francesco da Melzo), Isabella of Aragon as Pomona, c. 1497, Rome, Galleria Borghese; Leonardo da Vinci and his workshop, Madonna and Child, Detail, London, National Gallery; Pinturicchio, The wedding of Emperor Frederick III and Leonora of Portugal, Detail, Siena, Duomo, Libreria Piccolomini; second row from left to right: Bernardino Luini and his workshop, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Detail, Milan, San Maurizio; Bernardino Luini and his workshop, Saint Apollonia, Detail, Milan, San Maurizio; Leonardo da Vinci, Isabella of Aragon, Parma, Pinacoteca Nazionale; third row from left to right: Andrea Solario, Salome receiving the head of Saint John the Baptist, whereabouts unknown; Bernardino Luini and his workshop, Saint Mary Magdalene, Detail, Milan, San Maurizio; wrongly attributed to Bernardino Luini, Isabella of Aragon, Duchess of Milan and Duchess of Bari, Washington, National Gallery of Art

- Detail of Figure 1

- Attributed to Simone Martini, Maestà, Detail, Siena, Palazzo Pubblico

- Zanetto Bugatto, Crucifixion with Saints and Angels and Donor (The Sforza altarpiece), Detail, Brussels, Musée des Beaux-Arts

- Bianca Maria Visconti with the Sforza-Symbol of the three interconnected rings and the Imperial Symbol of the black eagle, Visconti-Tarot-Card

- Workshop of Sandro Botticelli, Pallas and Centaur, c. 1497/98, Florence, Uffizi

- Master of the Pala Sforzesca, Lodovico il Moro Sforza and his family, Detail, c. 1498, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

- Emperor Maximilian I and his second wife, Bianca Maria Sforza, c. 1507, Tyrol, Castle of Tratzberg

- Bernardino Luini and his workshop, Violanta Bentivoglio, the wife of Gian Paolo Sforza, Detail, Milan, San Maurizio

- Leonardo da Vinci and his workshop, "Mona Lisa", Vernon Collection

- Raphael, Raphael and his friend Francesco da Melzo, 1520, Paris, Louvre

- Titian, Giovanna of Milan and Aragon, Duchess of Paliano, Florence, Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti

- Agnolo Bronzino, Maria of Milan and Aragon, Margravine of Vasto and of Pescara,c. 1531-1533, Frankfurt am Main, Städelsches Kunstinstitut

- wrongly attributed to Giorgio da Castelfranco, called Giorgione, (he was already dead, when this portrait was made), Antonio of Milan and Aragon, Duke of Montalto, with his friend, the real painter of this double portrait, c. 1524, Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia

- Agnolo Bronzino, Isabella the Younger of Milan and Aragon, Princess of Squillace, c. 1534-1538, Frankfurt am Main, Städelsches Kunstinstitut

- wrongly attributed to Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, the painter is Leonardo da Vinci, Francesco II Maria Sforza, also called "Francesco il Duchetto", 1505, Washington, National Gallery of Art

- Sebastiano del Piombo, Vittoria Colonna as Judith, 1510, London, The National Gallery

Footnotes:

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Wer ist Mona Lisa? Auf der Suche nach ihrer Identität, Norderstedt 2003 (available only in German)

- Nowadays every second person depicted in an Italian Renaissance painting is wrongly identified; around every fourth Italian painting is attributed to a wrong painter, in: Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, "Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Wer ist Mona Lisa? Auf der Suche nach ihrer Identität, id., S. 16

- These mistakes are repeatedly done by art historians as shown in my article "The True Faces of the Daughters and Sons of Cosimo I de’ Medici", in: Medicea, rivista interdisciplinare di studi medicei, Firenze, n. 10 (2011)

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, Milan 2006, p. 81

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of Seventy of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, edited and annotated in the light of recent discoveries by E.H. and E.W. Blashfield and A.A. Hopkins, London 1897, p. 395; and n-tv.de. Der Tag – Kult und Kultur, Friday, 11 January 2008

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, id., p. 91

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, id., Appendix III

- Leonardo da Vinci, Eine Biographie in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen, Dokumenten und Bildern, herausgegeben und kommentiert von Marianne Schneider, München 2002, S. 187; and Anonimo Gaddiano, BNF, Cod. Magliabechiano XVII, 17, fol. 91r (Beltrami, Docvmenti, 163)

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, id., p. 96

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, id., p. 96

- see for example the lives of Sodoma and Botticelli in: Giorgio Vasari, Lives of Seventy of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, id., Volume 3, pp. 354-380 and Volume 2, pp. 316-319

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of Seventy of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, id., pp. 395-397

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of Seventy of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, id., p. 382

- n-tv.de. Der Tag – Kult und Kultur, Friday, 11 January 2008

- Guiseppe Pallanti, Mona Lisa Revealed – The True Identity of Leonardo’s Model, id., family tree of the del Giocondo, Appendix III

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, "Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, “Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza I: Bianca Maria Visconti – Die Stammmutter der Sforza, Norderstedt 2008 (third edition), S. 166-190

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza I: Bianca Maria Visconti – Die Stammmutter der Sforza, id., S. 181

- Gregory Lubkin, A Renaissance Court – Milan under Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 1994, p. 65

- Gregory Lubkin, A Renaissance Court – Milan under Galeazzo Maria Sforza, id., p. 65

- Bianca Maria Visconti

- Bona of Savoy

- Isabella of Aragon

- Beatrice d'Este

- Christina of Denmark (only in German)

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, Norderstedt 2010, S. 7

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, "Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, "Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, "Mona Lisa" und andere schwere Fehler – Eine Neubewertung der Kunstgeschichte in der Renaissance, in progress

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, id., S. 162-177

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, id., S. 325-345

- Leonardo da Vinci, Eine Biographie in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen, Dokumenten und Bildern, id., S. 273-274; and Charles Nicholl, Leonardo da Vinci – The Flights of the Mind, London 2004, p. 500; and Ludwig Goldscheider, Leonardo da Vinci – The Artist, London 1944 (2nd edition), p. 20; and Robert Payne, Leonardo, London 1978, pp. 292-293

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, id., S. 183-185

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, id., S. 244-245

- Maike Vogt-Lüerssen, Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci, id., S. 310-312