Der Alltag im Mittelalter 352 Seiten, mit 156 Bildern, ISBN 3-8334-4354-5, 2., überarbeitete Auflage 2006, € 23,90

Bilder-Galerie

Sophie Dorothea erblickte am 15. September 1666 das Licht der Welt und starb am 13. November 1726. Am 18. November 1682 hatte sie ihren Cousin Georg Ludwig von Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Calenberg (1660-1727) zu heiraten, dem sie zwei Kinder schenkte: 1. ihren Sohn Georg August (1683-1760), den zukünftigen englischen König Georg II., und 2. ihre Tochter Sophie Dorothea (1687-1757), die zukünftige Gattin des Soldatenkönigs Friedrich Wilhelm I. (1688-1740). Seit 1691 gab es keine Beziehung mehr zwischen den Eheleuten. Georg Ludwig verbrachte seine freie Zeit fortan lieber mit seiner Mätresse, der Gräfin Melusine von der Schulenburg (1667-1743), die ihm im Laufe der nächsten neun Jahre drei weitere Töchter schenkte.

Sophie Dorothea hatte sich um 1692 in den Grafen Philipp Christoph von Königsmarck (1665-1694), der aus einem alten märkischen Adelsgeschlecht entstammte und den sie bereits seit ihrer Kindheit kannte, da er im Haushalt ihres Vaters als Page gedient hatte, verliebt. Im Sommer 1694 hatten die beiden ihre Flucht von Hannover nach entweder Wolfenbüttel oder nach Sachsen geplant, aber ihr Plan wurde verraten. Seit dem 11. Juli 1694 war Königsmarck für immer verschwunden. Mit sehr hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit war er auf Veranlassung von Sophie Dorotheas Gatten ermordet und an unbekannter Stelle verscharrt worden. Sophie Dorothea, die zeitlebens leugnen sollte, dass es zwischen ihr und Königsmarck bereits vor der Flucht zu einer sexuellen Beziehung gekommen war, wurde wegen böswilligen Verlassens ihres Gatten geschieden und im Schloss von Alhden gefangen gesetzt. Nur ihre Mutter Eleonore d'Olbreuse durfte sie besuchen. Ihr Gatte, der selbst seit 1691 eine außereheliche Beziehung mit der Gräfin Melusine von der Schulenburg unterhielt, verzieh ihr nie, dass sie ihn verlassen wollte. So verbot er auch anlässlich ihres Todes am 13. November 1726 ausdrücklich jegliche Trauerbekundung für sie.

Sophie Dorothea, die sehr große Ähnlichkeit mit ihrer schönen Mutter Eleonore d'Olbreuse besaß, hatte eine sehr glückliche Kindheit verbracht. Von beiden Elternteilen wurde sie sehr geliebt. Am 18. November 1682 hatte sie ihren wortkargen, kühlen und verschlossenen Cousin Georg Ludwig von Braunschweig-Lüneburg, den ältesten Sohn ihres Onkels Ernst August von Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Calenberg, zu heiraten, von der seine Cousine Liselotte von der Pfalz sagte, er sei "trocken und kalt wie Eis." Im Alter von 16 Jahren hatte Georg Ludwig zudem bereits ein uneheliches Kind mit einer Untergouvernante seiner Schwester Sophie Charlotte gezeugt, was man in seiner Familie soweit wie möglich zu vertuschen versuchte. Seit 1691 lebte er schließlich hauptsächlich mit seiner Mätresse Melusine von der Schulenburg zusammen.

als Buch

als Buch und als E-book

Zeitreise 1 – Besuch einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt

als Buch, Independently published, 264 Seiten, 93 SW-Bilder, € 12,54, ISBN 978-1-5497-8302-9

und als E-Book

Nun auch als Buch

als Buch bei amazon.de: 552 Seiten, mit Stammtafeln und 292 sw Bildern, Independently published, 1. Auflage, ISBN 978-1-9768-8527-3, € 31,84 (großes Buchformat: 21 x 27 cm)

als E-Book bei amazon.de erhältlich, ca. 1.000 Seiten mit Stammtafeln und 292 Bildern, € 29,89

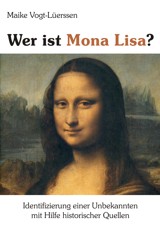

Neu: Wer ist Mona Lisa?

Wer ist Mona Lisa? – Identifizierung einer Unbekannten mit Hilfe historischer Quellen

als Buch bei amazon.de: 172 Seiten, mit Stammtafeln und 136 Bildern (130 Bilder in Farbe), Independently published, 1. Auflage, ISBN 978-1-9831-3666-5, € 29,31

Dritter Band der Sforza Serie

Die Sforza III: Isabella von Aragon und ihr Hofmaler Leonardo da Vinci

488 Seiten, 322 Abbildungen und Stammtafeln, €49.90 (Format 21 x 27 cm)